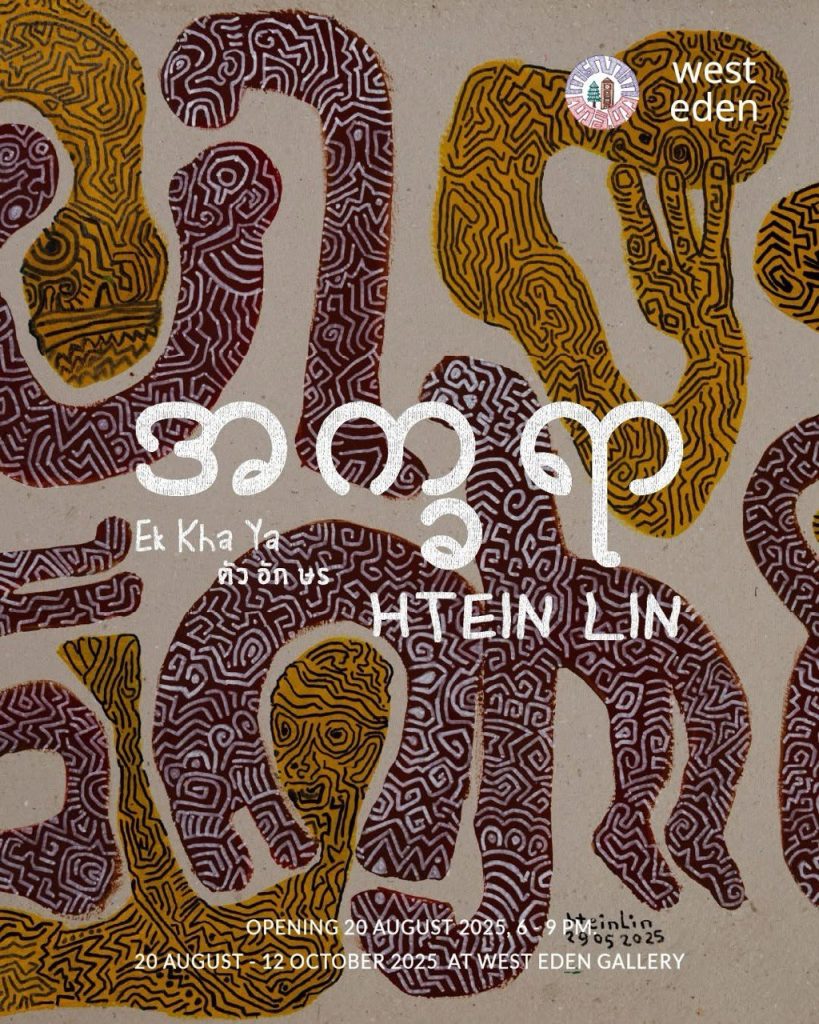

Ek Kha Ya

To read language is one thing, but to witness it burn, creep,

and breathe across a canvas is another.

During his almost seven years as a political prisoner, he painted secretly on scraps of prison uniform with smuggled pigment, transforming scarcity into invention. After his release, he carried that ethic into works on recycled cardboard and into paintings

that embedded loaded words like ‘Prison’, ‘Trust’, and ‘Rohingya’. Across these shifts in medium, one thread remains constant: the conviction that language itself can bear the weight of history and resistance.

The word ‘အက္ခခရာ’ (Ek Kha Ya) means ‘alphabet’ in Burmese. It explores Myanmar script as both material and method, a visual system encoding memory, resistance, and identity. Each character becomes a political form shaped by Htein Lin’s

trajectory as a student activist, political prisoner, and witness to national transformation. While Htein Lin’s name, meaning ‘bright moon’, is more than a poetic coincidence. His art shines through the shadowed histories of imprisonment, protest, and personal cost with a clarity that refuses to dim.

If Rohingya asserts visibility through repetition, Red Tape (Kyo Ni) (2019), confronts constraint. Letters here stretch and coil into serpentine shapes that twist across the surface, each band of red, green, and orange carrying the form of script. At once decorative and suffocating, these coils recall the bureaucracy of the colonial Burma that persisted under the Ne Win regime, red tape that once bound files now visualized as letters that strangle ambition and restrict movement. Yet even as they bind, the letters remain alive with motion. They writhe, lean, and press outward, as if language itself is refusing containment.

This conviction is palpable in Rohingya (2018), where looping Burmese characters crowd a recycled canvas made of newspaper, turning the very ground of the painting into an archive of words. The surface is already language before the brush touches it, and Htein Lin’s painted script collides with and overlays that printed text. The work confronts the state’s systematic erasure of the Rohingya people by insisting on the visibility of their name in Burmese language. At the same time, Htein Lin roots the work in cultural specificity.